Underground Railroad Free Press

News & Views on the Underground Railroad • Vol. XVII, no. 98, November 2022

Published bimonthly since 2006, we bring together organizations and people interested in the historical and the contemporary Underground Railroad. Free Press is the home of Lynx, the central registry of contemporary Underground Railroad organizations; Datebook, the community's event calendar; and the Free Press Prizes awarded annually for leadership, preservation and advancement of knowledge, the community's highest honors. Underground Railroad Free Press is emailed free of charge on the 15th of odd-numbered months. Please visit urrfreepress.com for more.

In This Issue

New Mapping Tech Gives Major Boost to the Underground Railroad Story

A County Sets a New Standard in Portraying the Underground Railroad

A Famous Neighborhood Sets a New Standard in Portraying Civil Rights

Articles

State Grants Boost Two Historic Sites

A Philadelphia Family Finally Recognized

One County Sets a New Standard

After Harriet Tubman died in 1913 and then others who had roles in the Underground Railroad began passing on, the nation’s memory of the Underground Railroad began to fade until by the 1960s most Americans younger than a certain age were unfamiliar with the Underground Railroad and the nation-defining history behind it. Underground Railroad Free Press research has shown that what began to revive Underground Railroad recognition was teachers in the 1960s on their own spontaneously adding the Underground Railroad to their curricula. Then school districts started doing the same and by 2017 a Free Press survey showed that nearly all of those younger than 50 had learned of the Underground Railroad in their schooling.

This in turn sparked intense interest in a few who began researching and writing on the Underground Railroad. Some of these researchers and authors became well known in the field while others labored quietly. One of the latter was the prolific Douglas Shepard, a professor of English at the State University of New York at Fredonia who after retiring about 1985 spent the rest of his life researching local history of Chautauqua County, New York, where he lived. About 2005, he turned his attention to the Underground Railroad. He died last year at 94. Along the way, others in the county joined the effort resulting in what today is almost certainly the most thoroughly revealed Underground Railroad County in the United States.

For example, says local researcher and project leader Wendy Straight, “I found the annual Baptist statements in local church records, and William Still's correspondence began appearing online. Other key sources were Judge Foote's Underground Railroad records with the County Historical Society, and the National Archives' surviving petitions researched by Judith Wellman. Doug deciphered the names and families, and I tried to keep up with mapping them. All of us were inspired by Fergus Bordewich's Bound for Canaan, where Fergus effectively told us: Use the internet and share your findings! Then, this past February, the gracious League of Women Voters in Chautauqua County asked me for [a] presentation.”

All of this ultimately led to the documentary film Underground Chautauqua: Three Freedom Trails. The enormity of the extent of the Underground Railroad in the county and of the amount of local research done on it came to light only last week with the premiere of this expertly done work featuring the huge amount of Underground Railroad history uncovered in Chautauqua County and surrounding areas in Pennsylvania and Canada. The county is located in the extreme southwest corner of New York state and, as the documentary shows, was a hotbed of Underground Railroad activity.

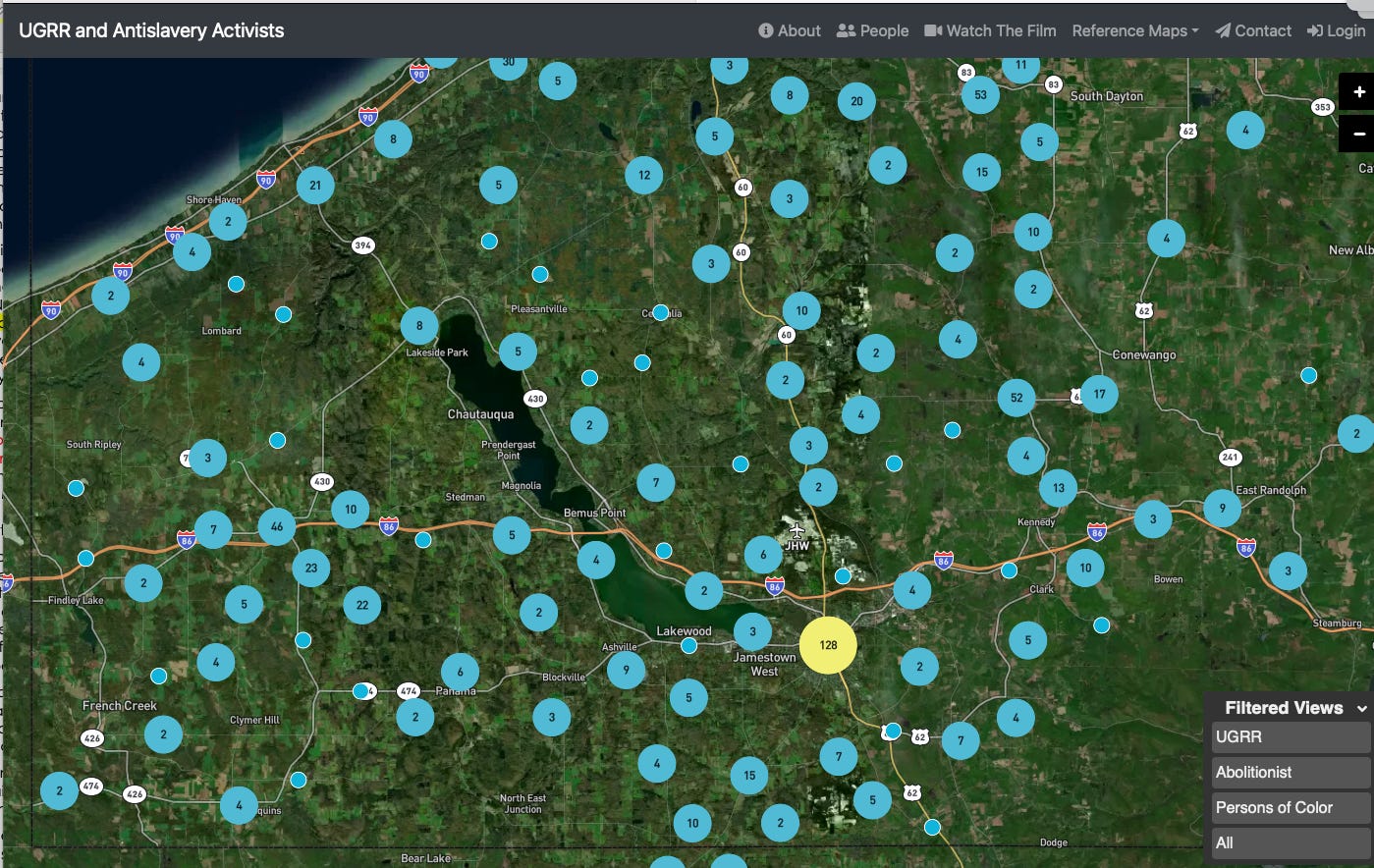

From its research base to its narration, to its outstanding interactive map, to its special effects, the production quality of this film is outstanding and comprises a new standard of Underground Railroad presentation. We’ve seen nothing else that comes close to its 1,100 historical figures, extensive historical detail and visual appeal. Hover your mouse pointer over an individual site on the map and a pop-up will inform you of the site’s history.

The project also demonstrates the value of public-private partnerships. Underground Chautauqua is available under the auspices of the Chautauqua County Office of the County Historian, which continues to play a useful hosting and advisor role.

It didn’t hurt that the film project has been guided by an All Star team. Three key people involved in the film’s production are past winners of Underground Railroad Free Press prizes. Wendy Straight won the 2013 Leadership Prize for “the diligence of her work uncovering, mapping and writing on the Underground Railroad in Chautauqua County.” Nicholas Gunner, film editor of Underground Chautauqua, won the 2015 Hortense Simmons Advancement of Knowledge Memorial Prize “for creating the best state Underground Railroad map yet, an interactive map of New York State Underground Railroad sites and historical figures.” And Judith Wellman was awarded the 2017 Free Press Leadership Prize for her “career-long leadership in the Underground Railroad community and for creating the Wellman Scale, the now accepted standard for evaluating Underground Railroad site and story claims.” Wellman contributed research and acted as Library of Congress liaison for the film project.

Plan on more to come in Free Press on the pace-setting breakthroughs happening in Chautauqua County, New York.

Links

Watch Chautauqua: Three Freedom Trails

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=khblPVcGMIM

Explore Interactive Underground Railroad map

https://themappingservice.com/project/ugrr

View Wendy Straight’s Underground Railroad presentation

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VUvlUvVqVsg

Access county archive of Underground Railroad materials:

https://chqgov.com/county-historian/county-historian

Fergus Bordewich’s book Bound for Canaan

https://tinyurl.com/BoundForCanaan

And Another Map

Founded in 1980, Village Preservation works to document, celebrate, and preserve the special architectural and cultural heritage of Greenwich Village, the East Village, and the North Houston neighborhood in New York City’s Manhattan Borough. Village Preservation has successfully advocated for the landmark designation of more than 1,250 buildings and has helped secure zoning protections for nearly 100 blocks. The nonprofit monitors more than 6,500 building lots for demolition, alteration, or new construction permits to notify the public and respond if necessary. Village Preservation also advocates for policies that promote racial and socio-economic diversity.

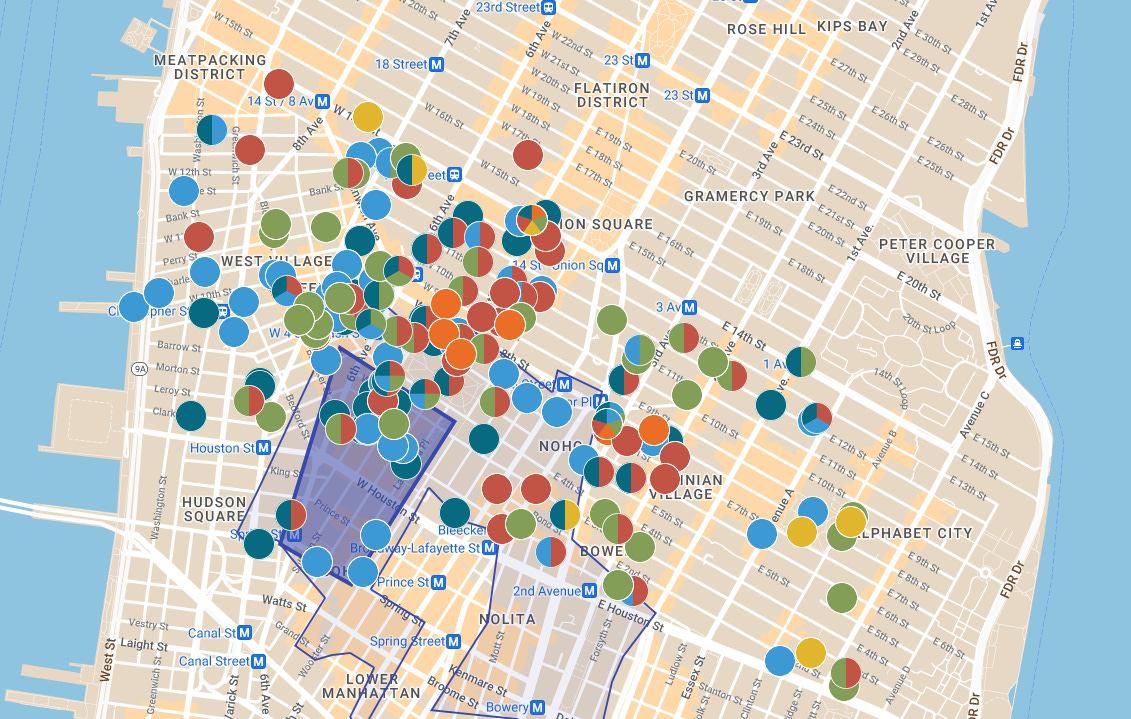

Village Preservation’s acclaimed Civil Rights and Social Justice Map has recently been revised and relaunched. Containing hundreds of sites connected to civil rights history found in Greenwich Village, the East Village, and North Houston, the updated map has made it easier and more engaging to learn how the course of history changed and the cause of social justice has been advanced in the area’s neighborhoods.

The map features dozens of sites connected to civil rights movements for African Americans, LGBTQ+ people, women, and immigrants, and locations from battles against anti-Semitism, and for equality for Asian Americans and Hispanic New Yorkers. Some are world-famous landmarks. Hover your mouse pointer over an individual site on the map and a pop-up will inform you of the site’s history.

To explore the map, visit https://tinyurl.com/NewVillageMap.

Grants to Free Press Mentions

The Maryland Historical Trust has announced grants awarded to twelve organizations from the Trust’s African American Heritage Preservation Program. One of these involves an Underground Railroad site previously written about in Free Press and another features one of the 2021 Free Press Prize winners.

Cumberland, Maryland’s Emmanuel Episcopal Church received $100,000 to improve lighting and ventilation in tunnels beneath the church that were used to shelter freedom seekers. In the international Underground Railroad community, it has become widely accepted that many claims of underground hiding places are exaggerations by those not aware that the “Underground” in Underground Railroad is only a figure of speech. But not in the case of this church which has compiled multiple accounts of the tunnels having been used to shelter freedom seekers. One tunnel leads away from the church to a river’s edge where the freedom trail resumes northward to nearby Pennsylvania.

Historic Sotterley, the nonprofit organization that owns Sotterley Plantation near Hollywood, Maryland, had been awarded $78,000 to repair a cabin that had been used as slave housing and to improve the pathways leading to it. Historic Sotterley won the 2021 Free Press Prize for Leadership for its exemplary Common Ground Initiative that brings together Black and White descendants of people who lived at Sotterley Plantation in the era of slavery.

Black Founders: The Forten Family of Philadelphia

By Stephan Salisbury

This article originally appeared in the Philadelphia Inquirer. Reprinted with thanks. An exhibition on the Forten family will open at the Philadelphia Museum of the American Revolution on February 11, 2023. For more, visit amrevmuseum.org/ at-the-museum/exhibits.

When Kip Jacobs, 63, was growing up in West Philly, his great-grandmother was the only family member who talked much about their ancestor James Forten, a free Black man who became a wealthy sailmaker in post-Revolutionary War Philadelphia.

“I knew that he had saved nine people from drowning in the Delaware, according to my great-grandmother, Daisy Parker,” Jacobs said. But there wasn’t much talk about abolitionism, or Forten’s old friends, like Absalom Jones, founder of the African Episcopal Church of St. Thomas, or William Lloyd Garrison, editor of The Liberator newspaper.

Grandmother Parker, Jacobs added, “would say that he was a famous man, he was a businessman.” But that was about it. “Mind you, I just caught glimpses of this. She was 90 when I was 5 or 6.”

When Jacobs’ daughter was assigned a school report in 2007 about someone famous, he “didn’t have a whole lot of information” to share about the “famous man” in the family. They went to the library.

In “the F section,” he said, they stumbled across historian Julie Winch’s 2002 Forten biography, “A Gentleman of Color,” a chronicle of entrepreneurship and civic engagement that’s a milestone on the path toward a more inclusive and comprehensive understanding of the birth of the nation.

Jacobs emailed Winch immediately, and they’ve been in touch ever since. The two finally met earlier this fall at the behest of the Museum of the American Revolution. Both were in town to assist planning for the museum’s upcoming exhibition, “Black Founders: The Forten Family of Philadelphia,” which opens Feb. 11.

“If I learned about the connection earlier, I think it would have changed my life,” Jacobs said. “I would have taken things a lot more seriously, because I’ve had a lot of fun along the way, and it’s been a great learning experience.”

His daughter nailed her school paper for an A.

A professional photographer who lives near Chicago, Jacobs arrived in Philadelphia bearing an important artifact he is lending to the museum for the exhibition — a Bible used to record family history. Notations in its pages meticulously document everything — from the birth of James Forten Jr., Nov. 15, 1812, through James Jr.’s marriage to Jane Vogelsang in 1839, and all the way to the 1995 birth of Taylor Jacqueline Rodriguez Jacobs, daughter of James Forten’s great-great-great-great-grandson Atwood “Kip” Forten Jacobs and Marina C. Rodriguez.

Jacobs also visited Mount Zion Cemetery in Lawnside, Camden County, where 14 of his ancestors are buried. He was shown around by Dolly Marshall, a cousin and fellow Forten descendant, who is a preservationist and genealogist — the self-confessed “family detective,” who learned of her Forten family connections several years ago.

Forten descendant Kip Forten Jacobs looks through the family Bible on Oct. 19. The Bible is on loan to the Museum of the American Revolution for an upcoming exhibit.

“A lot of people don’t know the Black founders,” she said, “with James Forten Sr. and his pivotal role as a Founding Father starting from Revolutionary War time. It’s very meaningful to me ... to know that there were a lot of contributions and a lot of efforts made by the African American community in Philadelphia.”

The Bible was a wedding gift to James Forten’s daughter-in-law from St. Philip’s Church in New York City, where she was baptized, Winch said.

The Rev. Peter Williams Jr. of St. Philip’s had married James Jr. and Jane Vogelsang of New York; a “happy and sad” event, Winch noted.

“It took place at the bride’s home because her mother was dying of tuberculosis. And the same day the couple was married, the bride’s mother died.”

The Forten Bible, never before seen in public, is one of several family artifacts that descendants are loaning for the exhibition.

A Philadelphia-made table that stood in the home of James and Charlotte Vandine Forten on Lombard Street between Third and Fourth Streets is being loaned by Marcus Huey, a Forten descendant living in Phoenix, and his wife, Lorri. The table has been in the family for seven generations.

The Hueys are also lending two samplers made by James Forten’s daughters Margaretta and Mary Isabella, in 1817 and 1822, a silver spoon from the 1840s engraved with the letter “P,” and a candle snuffer — both owned by Philadelphia’s Purvis family.

The Forten writing table and the two samplers, Huey wrote in an email, were passed down from James Forten to daughter Harriet, then to her son, CB Purvis, then to his daughter, Alice Hathaway Purvis, then to her son, the Rev. John Loring Robie, then to his stepdaughter, Sidney June Simpson (Huey’s mother), and finally to Huey.

The Forten and Purvis families are intimately intertwined. Harriet and Sarah Forten — two of James and Charlotte’s daughters (they had nine children) — married brothers Joseph and Robert Purvis, abolitionists who worked with William Lloyd Garrison and James Forten in establishing the American Anti-Slavery Society. They also worked with William Still on managing the Philadelphia hub of the Underground Railroad.

Charlotte Forten and three of her daughters — Harriet, Sarah, and Margaretta — were cofounders of the Female Anti-Slavery Society, the first integrated women’s abolitionist organization in the U.S.

It is impossible to understand the evolution of the nation or the social and political roles of Black Americans, without addressing the Forten family and their relations with families such as the Grimkés and the Purvises, argued Matthew Skic, the museum’s exhibition curator. This exhibition is only one of a number of museum projects tied to the protean Forten family of educators, poets, photographers, writers and activists.

James and Charlotte Forten’s granddaughter Charlotte Louise Bridges Forten Grimké, a poet and educator, was also a writer and activist. Her best known work remains her diary, “The Journal of Charlotte L. Forten,” still in print. James Forten was also good friends with his neighbor, composer Francis Johnson, who set to music his daughter Sarah Louisa Forten’s poem, “The Grave of the Slave.”

“It was published in [Garrison’s newspaper] The Liberator,” Winch said.

“When it was set to music, it became a standard at anti- slavery rallies.”

When Winch started her research on Forten over 20 years ago, she said there was minimal information.

“I dreamed about this,” she said about the exhibition, “about him getting the visibility he deserved.”